Hello there and welcome, old and new subscribers! This week, I'm posting an article first published on here, and which I think it's still relevant today. It's about the concept of Instability in my country of origin (Italy), and in my new home, the Netherlands. I chose 2 different angles, the employment issue in Italy, and the myth of Dutch tolerance. Don't worry, it's short and sweet, more an introduction than an in-depth analysis.

As for the promise/threat, in the next weeks/months I'm going to publish a short novel (or a long short story, I haven't made up my mind yet), which I began writing in 2020. It's a silly experiment with no literary ambitions at all, that I hope you'll find entertaining.

More news in the following 2 weeks. Stay tuned!

Italy – Perpetuum immobile

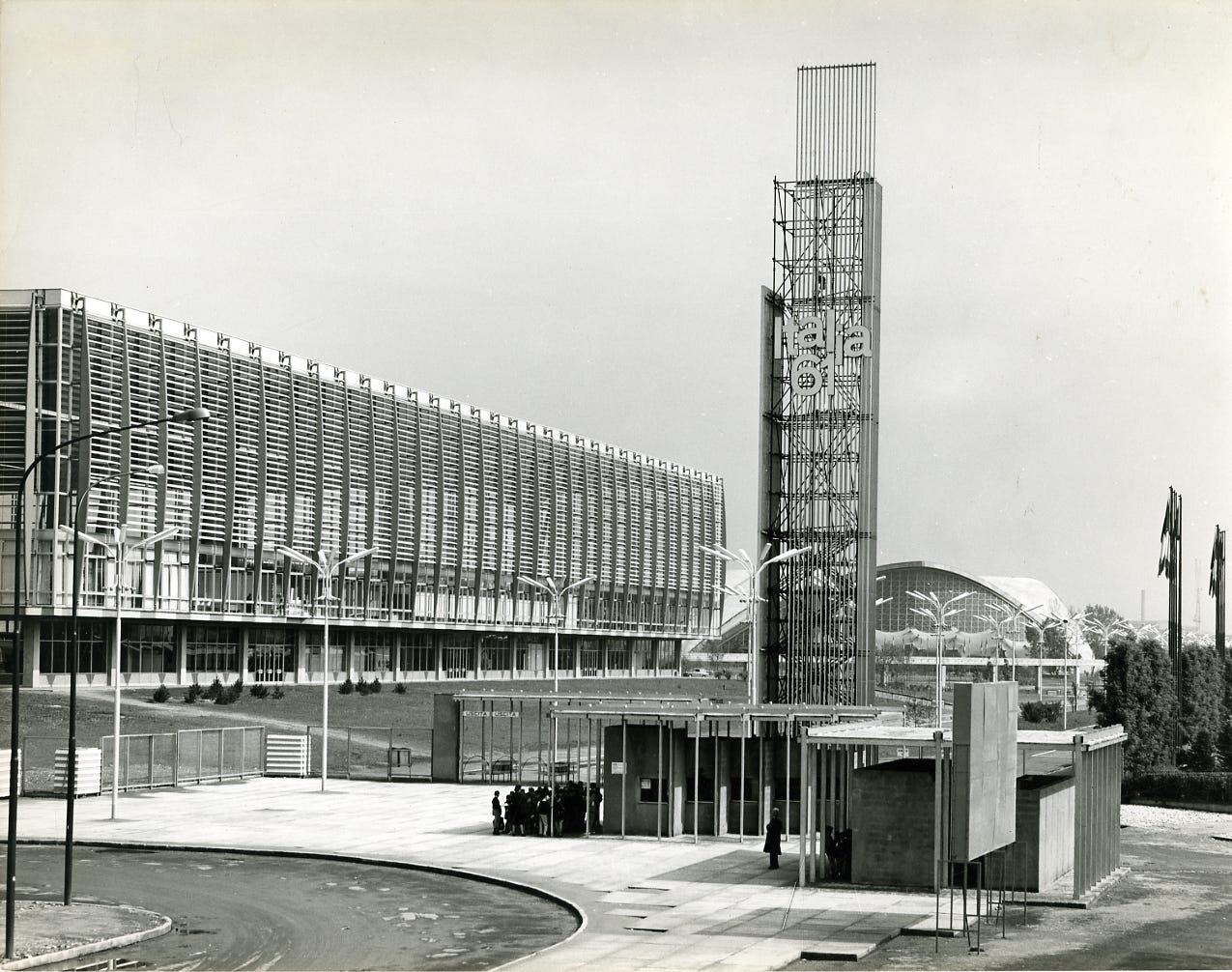

In 1961, a booming Italy celebrated the first 100-year anniversary of its unification. So many momentous events (two world wars and a 20-year long fascist dictatorship in-between, to name but a few) had passed since then, and it was a very dynamic society that greeted a new era of economic prosperity and hope for an increasingly better future.

Yet, it is possible that – in those same years of social mobility and flourishing entrepreneurialism – the seeds of fear of instability (instabilità) were sown.

In a woefully mistaken understanding and application of the noble concept of social welfare (or, most likely, in order to gain votes), many jobs were created in the public sector and people started to value being secure in their jobs (i.e., never ever letting go of them until retirement) far more than enjoying them, or – at the very least – more than being generously paid. The utopian island of posto fisso1 was born, a dream to which – apparently – many still cling.

Posto fisso can be loosely translated as permanent position, though this phrase doesn't convey all the nuances it does in Italian – people can have permanent positions, while frequently changing the places and roles they work in during their lives, whereas a posto fisso is the one you take (or, more often than not, someone else – a relative, a politician, a connection – secures for you, in exchange for more or less unsavory favors) and keep for life, in a kind of till-death-do-us-part, monolithic pact.

Instability for us carries a hefty degree of menace in itself. In a country geologically, politically, economically challenged like Italy, where a distinct lack of civic culture and a widely spread amoral familism2 have been a constant throughout its brief history of unification, and way beyond, instability is regarded as something to avoid at all costs.

People want security no matter what, at the cost of sacrificing their own job satisfaction and – on an increasingly wider scale – fairness, meritocracy, social mobility, national competitiveness.

Even the liberal professions experience this kind of immobilism, when the children follow in the family footsteps – inheriting their parents' household names and clients' portfolios – and therefore don't learn to fend for themselves. Freelancers are seen as reckless dimwits, heading down the inevitable road to starvation.

Couple that with an overly complicated tax system and we have the reason why people long for the warm, if suffocating embrace of posto fisso.

The predictable results of this mindset were already apparent in the seventies, but they are, even more so, painfully felt nowadays, when a new wave of highly skilled and well-educated people can no longer aspire to obtain a posto fisso and are leaving the country in droves, in search of better prospects and more dynamic work cultures, moving mostly to the UK, Germany, Northern Europe, just like in the 19th and early 20th centuries when their great-grandparents moved to the Americas and Australia.

Surprisingly enough, Italy is still there, one of the largest economies in the world, but how long can a country allow such a brain drain and lose its most precious resources?

It wasn't always like that. In a distant past, Italians had been merchants and intrepid navigators, always ready to brave stormy oceans and commercially conquer faraway lands. Instability was accepted as part of our everyday lives, it was a matter-of-fact way of life, as life in its essence is ever-changing, unpredictable, unstable.

Finally accepting and embracing instability, seeing it as a chance for a brighter, better and fairer future, could be one of the answers. Becoming reliable on our own strengths and – equally or even more important – building mutually trusting business and social relationships, establishing solidarity way beyond our closest families' and friends' circles, could bring a fresh perspective, provide a new start for exciting ventures and – albeit slightly ironically – lay a path to a less unstable future.

The Netherlands – Going with the flow

In the Netherlands, we don't seem to be too bothered by instability (instabiliteit) – we built our country on sand and water, learnt to live with them and exploit them to our advantage. It has been neither easy, nor straightforward, and it has cost us blood, sweat and tears for centuries on end, but now we're able to rein in those unpredictable elements.

We even named our country according to its peculiar geological features. We could say that not only do the Dutch live on the edge, many of us live under it3.

The sea still defines our lives, as it did in the past. We were whalers, merchants, navigators. The overseas expansion of our geographical borders had a very dark side to it – wars, colonial exploitation, slave trade. But at home, we succeeded in developing a relatively tolerant society, open to people who faced religious persecution in their countries, such as the Sephardi Jews from Spain and Portugal, and the French Huguenots.

The foundations of our modern identity were made stronger during the Gouden Eeuw4 (the Golden Age) in the 17th century, when we dominated many of the trade routes, the sciences, the arts.

In the 20th century, we finally lost our empire, survived the Nazi occupation, and emerged again on the world scene as a dynamic and exciting, albeit small and over-populated nation and, quite credibly, a shining beacon of emancipation, tolerance, acceptance.

Was it, though? During the noughties, what we thought of our society was being shattered to the core by the consequences of 9/11 and two local political assassinations5. Suddenly, a new sense of disorientating instability became apparent. We had to come to terms with the fact that, most probably, we had mistaken emancipation with integration and that our unshakable pragmatism was considered too overreaching by a not so small minority of Dutch people.

We are aware that our peculiar geological landscape is something we have to face rationally on a regular basis, and that we will have to work hard around it every day of our lives, if we don't want to be swept away by the constantly rising sea levels. This kind of instability may even look less scary, because it can be monitored and checked. But when it comes to people, a merely dry scientific approach isn't at all helpful. Thinking in terms of numbers or in terms of ‘us versus them’ could actually deepen the sense of fear and instability.

This is the new challenge we have to face nowadays: to reevaluate and redefine our core values of openness and inclusiveness, in order to rebuild those solid grounds that allow our society to withstand instability.

https://theitalianist.wordpress.com/tag/employment/

https://edwardcbanfield.org/2012/07/20/the-washington-post-mentions-amoral-familism/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amsterdam_Ordnance_Datum

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dutch_Golden_Age

Those of far-right politician Pim Fortuyn, and film director Theo Van Gogh

Thanks for reading! If you liked this post, you can share it, leave a comment, or buy me a tea. I'd be very grateful to you, I'd appreciate it more than I can express!

I love a solid bit of cultural exegesis, Portia - and here we get two. Dank u vell. <3

But I am mortified to learn that, as a *libera professionista,* Italians view me as a "reckless dimwit, heading down the inevitable road to starvation."

Is it really true? Because if a *posto fisso* is a pipe dream for an Italian, it's even more impossible for a non-Italian in Italy.

On the other hand, my freelance income, while not strictly under my control, approximates a full-time Italian monthly stipendio, so I am overall content with that.

It's still far less than my American income in some years ... but then I'm here, and all in on an Italian quality of life, for which there is absoluately no stateside comparison.

I do feel truly sorry for all the miserably employed Italians who do not change jobs. It's a lot like the US housing market though - once you cash out, you can never get back in again.

You're giving me cravings for strong Dutch kaffee with a plate of kaasebrod.

This was fascinating -- I was familiar with some of the cultural points you explore, but not all. The French too have been quite fond of stable jobs, but I don't think it runs as deep or that there was so much corruption in handing them out. That all is changing to some extent with the under-40 generation.